When Frederick and Samantha walked into the old farmhouse, the first thing Samantha noticed when they rounded the corner was the nail sticking out of the wooden walls.

“It’s small but it’s a nice… open space,” Frederick said.

They felt the room’s potential, but any excitement was marred when Sam saw that nail.

“There’s a huge nail.”

“I can patch it. It’s not a big deal.”

“Makes it feel like a trailer park.”

“You don’t think that may be taking it a bit far?” He smiled at her, trying to tease her from the mood.

“Hmmf.” Then after a pause. “These old mantels are nice. Too bad they’re only decoration. I’d prefer gas logs.”

Husband and wife stood for a moment, each entertaining private thoughts.

“It’s much too small,” she said. What she thought was, too tacky.

“Why don’t we look around?” And they set off in opposite directions until Frederick heard his wife scream.

“What is it?” He called leaping back to where she stood before an old mantle.

“Spiders! Everywhere.”

“Goodness,” Frederic said. “I don’t know if I’m relieved or….”

“Or what? Say it.”

“For god’s sake, I thought you’d been bitten by a snake or something.”

“Just look at the webs.”

“Cobwebs, yes. But no spiders. Maybe once, but not now. Anyway, I can get rid of them in two minutes with a broom.”

Sam shuddered. Frederick raised his palms in a gesture, both impotent and questioning.

“Just look at that.”

“What?”

“Who in their right mind would disrespect an antique so badly?” she said in a strained, tense voice.

“What are you talking about?”

“The ring! Look at the mark left on this old mantle. Who would do that...?”

“Well…”

“Well, indeed. I think we should look at another house.”

“I rather like it.”

“You only like the price. If it wasn’t so cheap, you wouldn’t look twice. It’s ugly. It is not the house I want.” She paused and caste her glance around. “What on earth? Oh no. Blue splotches on the floor? Well, I never. Well, that seals it; we’re not buying. Too terribly tacky.

It was only after they’d returned to the hotel, and Frederick had left his wife, in the darkened, curtain-drawn room—I have a headache; that squalid, tacky house had no air-conditioning—that he drove to the county courthouse and began asking the questions, trying to soothe his Northern accent to match the southern twang of the locals.

“Oh, you mean the house on Hat Creek Lane. Need to ask old Mister Jeffreys.”

Frederick didn’t locate old Mister Jeffreys until the following day, and by that time Samantha was well past ready to leave the “godforsaken redneck land.”

But Mister Jeffreys invited Frederick in, Samantha having remained in the air-conditioned hotel room, warding off a migraine.

Mister Jeffreys shuffled him to the back porch and there he sat him down on a glider while reaching to his side and pouring a drink.

“Have a whiskey.”

“Oh no, I don’t—”

Jeffreys pushed the dirty, smudged glass closer. “Good for what ails you.”

Frederick hesitated then took the glass to his lips. Then he asked Jeffreys about the house. He didn’t really know what he was looking for… perhaps a reason not to buy it, a faulty foundation or some such. Or maybe some magical reason why he would be able to convince his wife to like the house that was softly speaking to him.

When Mister Jeffreys began talking, spaced with intermittent and generous swigs of whiskey, there was a faraway look in his eyes, and he didn’t stop until dusk fell.

Twenty-six years ago

“Well, this is your new home,” she said, lifting a scrawny, mangy dog from her car into her arms. “You’ll love it here. We all do.” By “we all” she meant herself, a small, smooth, sleek black dachshund, a whole host of bugs, birds, snakes and the like.

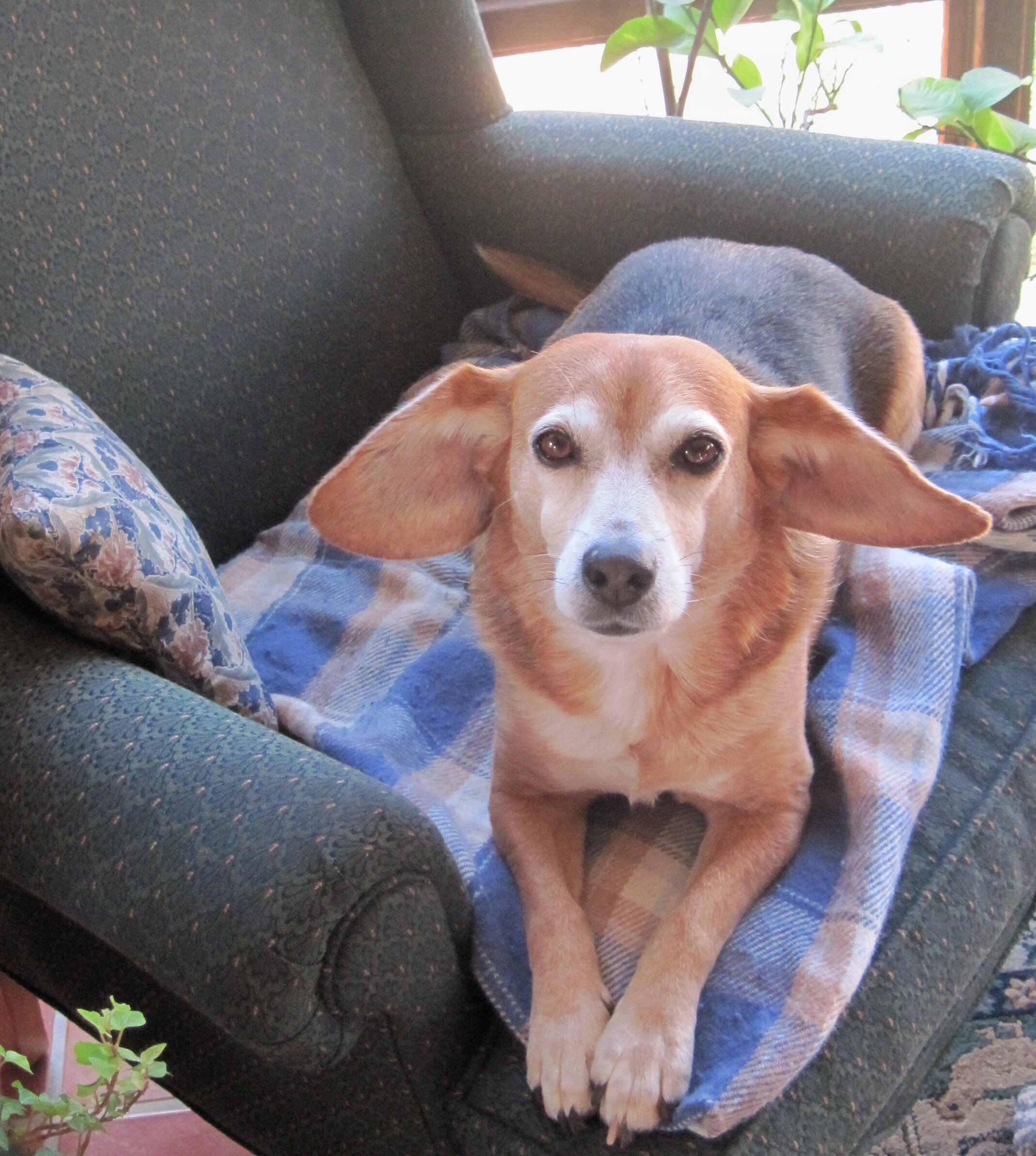

The little dog hung her head low, her eyes wary; her expression flecked not so much with fear as it was without hope.

“I’m going to name you, Chance. For what are the chances that’d I have found you?” The human asked, as if she’d found a bag of gold coins instead of a mangy beagle. She set Chance on the grass to use her own legs.

“Wandering lost and all alone. But not anymore. Come this way,” she called. “It’s not very grand, but you know what? We’re happy. At least… we are now,” she said smiling at Chance, who looked like maybe a Chihuahua had slipped into her ancestry at some distant point.

“Meet Flash! He may be small but he has more personality than three German shepherds and two Goldens put together.” Flash waved a thin whip tail back and forth as he nosed the newcomer, his stance erect, his energy excited. “And here’s our yard. Isn’t it just the most beautiful thing you’ve ever seen?” Out back the “most beautiful thing you’ve ever seen” consisted of a long narrow strip of grass with various stages of flowers and shrubs being planted. Some remained in black plastic containers, while others stood proudly in a garden with fresh newly dug dirt mounded around them, and still others sat in terra cotta planters. Bordering the yard were low gentle mountains and wild flowers waving a gentle welcome.

After a week, little Chance followed the human everywhere, already bonded, and played with Flash for hours out in the yard as late afternoon sunlight filtered down through the leaves that had begun turning yellow.

Only now could she admit that she and Flash had been sad. They were both grieving and without realizing it, they had needed this little Chance. Perhaps they thought they’d given her a second chance at life, rescuing her lost and lonely self. But really, the human knew that rescue was a two-way street. So, too, was love.

The days grew shorter as autumn came, while the light’s clarity intensified. Outside a chorus of crickets chirped like angelic beings, while down the road, someone was burning leaves. She called to the dogs who came dashing outside and she wondered about all the people who’d walked this earth before they had, and who would trod the same steps after they had passed from this world.

While Chance’s mange had cleared, her skin still itched. The human made a solution of hydrogen peroxide and vinegar to dip Chance’s feet in after outings. Once, when she made the solution in one of her French copper pots, it turned blue and Chance’s little blue feet flitted about, leaving indelible blue prints across the floor.

When winter arrived, she brought all the plants inside, settling them into corners and lining the two mantles. She watched her breath in the chill of morning as the ground sparkled with early frost. Flash flew past her, through the dog-door, his smooth-coated body shivering with cold. But Chance stood beside her, sniffing the morning air, steeped deep with scent. The two dogs were inseparable, spooning and licking each other in the dog beds that covered the floor, and at night the three of them all slept together under the quilts of the main bed, as the wind blew and bent the bare tree branches outside their window.

She tended and watered the plants just as she had outside, spilling water often onto the rugs and leaving rings underneath the liners on the mantles. But she didn’t care; she only cared for the plants. Neither did she care that the spiders had taken up residence in the corners of their home.

“The Japanese have a saying, that a home filled with spiders is a home filled with creativity,” she had said to Flash, as he peered up at her one summer day when she scooped up a spider and took it outside. But now she looked out to the steel-gray of an overcast sky and she left the spiders alone.

Then one gelid morning, she woke from a dream of someone knocking incessantly on her door. Chance’s head and neck strained forward as she coughed and gagged, coughed and gagged. She didn’t seem aware of anything and when she turned her head, the human saw the bloodshot panic in her kind brown eyes. A trip to the vets and a dose of antibiotics cleared the pneumonia.

But the next trip to the vets would not be as brief and not for pneumonia. She and Flash lay huddled together on the sofa of the emergency clinic as Chance remained behind the closed doors hooked up to fluids and morphine. The snake had not struck her once but twice, and her blood refused to coagulate, oozing now from every orifice. With a somber face, the vet warned that chance of survival was slim, and after each successive blood transfusion, her chances dropped exponentially. She had already undergone three.

After the doctor left the sterile room, the human buried her face into Flash’s smooth coat and cried. Chance was a young dog. The thought of losing her like this was not bearable.

It was the South African doctor who suggested they stop the blood and try instead a plasma transfusion. And on the next day when they wheeled Chance into the examining room, her head was up. Her eyes had lost the distant vacant look and now they focused on the two who loved her. Her body was less swollen, although it remained darkened with blood.

Two weeks later, Chance came home, taped up with bandages. And a week after that, she and Flash ran ducking in and out of bobbing flowers, as a soft spring breeze blew clouds across the sky.

Joy had returned to the small home. And loved permeated the air.

Weeks turned to months and months to years, and when Chance started drinking large amounts of water, the human took her in to the vets and was told what she already had guessed. Chance’s kidneys were failing.

The first time she pinched up her flesh and stuck the needle in, Chance flinched but remained stoic, perhaps understanding that the fluids would help her. The human couldn’t hold the fluid bag and Chance at the same time so she hammered a large nail into the wall of the house above the chair where she and Chance sat together in their morning ritual, a moment poignant in sorrow and tenderness, but most of all love: Chance licking food from a little lid and her talking to her, buoying up her spirits, sometimes singing songs of love. And how she clapped and danced as Flash and Chance wagged and wiggled when the daily fluids were finished, just a few centiliters and few moments of time, special moments because they were focused and as always, all together. And all of the moments were good moments because they were filled with care and respect. But most of all, they were filled with love.

Before the heavy days of summer when it was too hot to take the dogs with her, she drove with them to the crafts store and bought a beautiful set of wind chimes. Out back in their yard, she sat with the dogs and felt the breeze touch her bare arms. Chance rubbed up against her.

“When you were sick, I sat with Flash, and we were very still. It was when the breeze touched my arm that I knew. It was then that I knew you would be okay. Either living or dead. But okay, if you know what I mean. I could feel you in the breeze.”

Chance yawned and stretched and Flash let out a playful “Yip!”

“It’s like each of us is given a mystery in life to solve. Different mysteries all of us. But the answer to each is always the same. The answer is always love.”

She stood and watched Chance staring fixedly with pricked ears into the hole that Flash was digging with great intent.

“I’m going to get the ladder and climb that old pine tree. I’ll hang the chimes high so the breeze will always touch them. Then when you’re …” She paused feeling her throat constrict a bit as she watched the two dogs engrossed in digging. “When your physical body has left us… I’ll still be able to feel you. I’ll still hear you. And I’ll know you’re right here always.”

Then the day came. And the vet came out. come, and human and Flash sat on the bed beside Chance and said goodbye. The window was open and the breeze came in and she told the little, once mangy, dog how very, very grateful she was that she let her bring her into her home, and she told her how very, very much she loved her. She felt the breeze on her arms and the sunlight touched the three of them.

Afterward as the ragged, difficult days passed, she would look to the blue spots on the wood and feel the pang of love and longing, but somehow, also, a strange kind of comfort. Later that month, she drove with just Flash and together they bought a small oak tree to plant where Chance had taken her last steps. She stood with Flash and scattered Chance’s ashes around the tree. Often together as the light changed and a setting sun caste a golden glow across their yard, she and Flash would sit side by side before the little tree, and she’d say to Flash:

“One day that tiny tree will be a majestic oak.” And to the tree she’d say: “Grow tall, grow strong and bring welcome shade to the creatures of this earth. You were planted with love, and in memory of a much loved little dog. Long after we’re all gone, you’ll stand giving beauty and comfort.” And she and Flash would sit a long time and feel the love of the tree.

The Present

Frederick left when old Mr. Jeffries started to snore. But as the old man had rattled away about one nonsensical thing after another—spiders, dogs, trees and love—Frederick had, for some odd reason, made up his mind to buy the house. He’d let Sam call the shots and have things her way, but he was determined that before he died he would follow his dream to live in the country before he died.

Samantha called Dodson Pest Control and had the house sprayed and rid of rodents and insects. Frederick pulled forth the offensive nail and sprayed polyurethane on the mantels. But there was one decision he fought.

“We need to cut down that tree,” Sam said one morning, stirring Equal into her iced tea, and pointing outside.

“The oak?”

“The Hendersons put in a gi-normous swimming pool, and I want one too.”

“But…”

“That’s the only spot big enough. The tree has to go.”

“It’s such a big, beautiful tree, and it provides the house needed shade and the squirrels and birds love it … it always has so many acorns, and….”

The next week the tree company came and cut down the oak, but not before asking if the couple was certain. “It’s such a beautiful tree. It’s quite healthy too. People pay good money for established oaks like this.”

“Yes, we’re certain,” Samantha snapped. “We’ve other plans.”

A few weeks after the oak came down, the bulldozers began digging the pool.

One evening Frederick stood staring out at the huge pit and the upturned earth beside it. The chorus of crickets he’d always hear had not been as vibrant since the pool construction began. He’d put on his wool shirt and he could still smell the mothballs his wife used.

“What is it?”

“I don’t know I thought I heard church bells ringing.”

“I wish you’d come to church with me. Pastor Robert said today that God watches over us and won’t let the immigrants or Islams take over. God will make sure they’re all deported back where they belong. I’m sure they’ll get good homes.”

But Frederick wasn’t listening. He heard the bells again and he was walking in their direction.

“What is it?” Sam asked with urgency. “You’re acting strange. You should go to church with me. You should—”

She was still talking when he answered her, but whether he answered her in his mind or aloud he didn’t later know: “I don’t know… something. Each of us is given a mystery in life to solve. But the answer to each is always the same. The answer is always love.”

The chimes sang to him and he walked out and over to the edge of the dirt mound. He was about to turn back when he saw it. He began pulling the dirt away, and when he’d finished the tiny sapling popped back upright.

“Well, I’ll be. You’re the result of all those acorns. Well, I’ll tend to you. I’ll see that you’re loved….”

The chimes rang again and Frederick thought to himself how beautiful they were, and… somehow eternal.